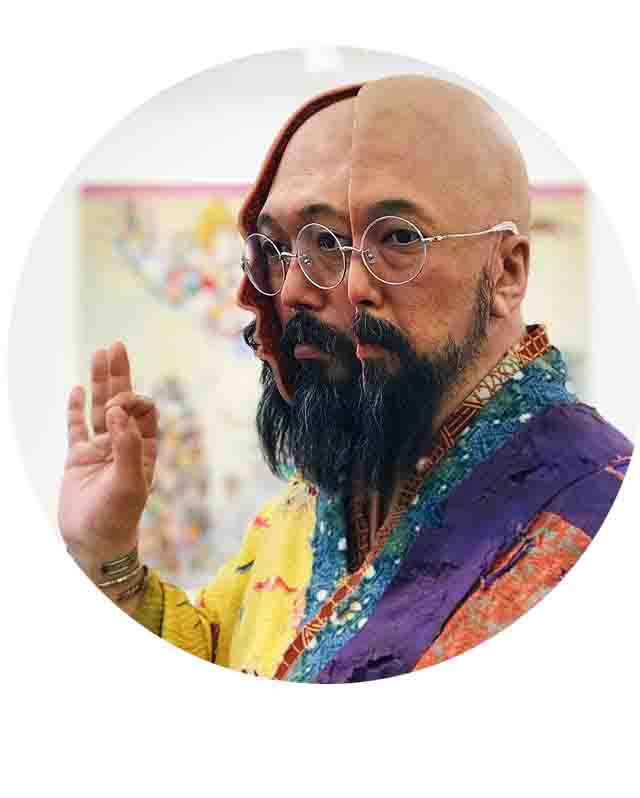

Takashi Murakami

Takashi Murakami

Takashi Murakami

Childhood

Born In 1962, Murakami’s father was a taxi driver, and he was a homemaker for his mother. His mother, who studied needlepoint and designed textiles, had an immense effect on the interest of Murakami in the arts. He also made his parents compose reviews of exhibitions he had attended. He was forced to go to bed without dinner if he refused. Raised in such a highly competitive environment, Murakami quickly learned how to think and compose. His later fame as an acerbic art critic was partially informed by these abilities.

Murakami grew up hearing his mother reassure him that he would not have been born had the U.S. dropped another nuclear bomb. In the decades following WWII, the omnipresence of the destruction and the subsequent U.S. presence in Japan had a profound impact on the artistic evolution of Murakami. Japan created a national identity during Murakami’s childhood that resurrected traditional Japanese culture and imposed immense pressure on its population to produce in order to compete both economically and culturally with the West. Murakami’s childhood hobbies, which ranged from attending Buddhist rituals and taking Japanese calligraphy courses to visiting museum exhibits of masters such as Renoir and Goya, reflected this hybrid focus on traditional Japanese culture and Western influences.

While he developed an early appreciation of both traditional Japanese culture and modern European art, during his formative teenage years, Japanese animation had the most important influence on him. This explains why a large part of his works are devoted to the otaku audience, a subculture obsessed with dystopian and fetishistic imagery. In anime and manga, these recurrent motifs coincide with the reluctance or even unwillingness of otaku supporters to engage in the real world or apply social skills. The otaku subculture is related directly to post-WWII Japanese society by Murakami himself.

Early Training and Work

Initially interested in studying animation background art, Murakami enrolled in the department of the prestigious Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music in 1980 in the nihonga (a traditional Japanese painting style that draws on elements of Western art), where he remained for a master’s degree (completed in 1988) and a doctoral degree (completed in 1993). He also studied animation production outside of school while diligently learning the old techniques at university, and continued his knowledge of the contemporary art world through visiting exhibits and the visiting artist program of his school.

Initially interested in studying animation background art, Murakami enrolled in the department of the prestigious Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music in the nihonga (a traditional Japanese painting style that draws on elements of Western art) in 1980, where he remained for a master’s degree (completed in 1988) and a doctoral degree (completed in 1993). He also studied animation creation outside of school while diligently learning the old techniques at university, and continued his knowledge of the contemporary art world through visits to exhibits and the visiting artist program of his school.

The early works of Murakami show the realities he grew up with, exploring Japan’s complicated post-WWII relationship with the U.S. Polyrhythm (1991), for instance, uses plastic World War II toy soldiers, refers to the atomic bomb in Sea Breeze (1992). These works display his early development of a style that is humorous and seemingly light, often referring to a more cynical place.

Mature Period

In 1994, Murakami traveled to New York City on a fellowship from the Asian Cultural Council to participate in the International Studio Program of the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center. Murakami, alone and fairly depressed in New York, was surrounded by the demands of the gallery system and the American art market. There, he realized that he had to abandon his excessively intellectual Japanese concerns in order to survive in this world, and to show a more simplistic brand of himself and his art as quintessentially Japanese. Therefore, this moment marks a radical turning point in his career. Previously, his work focused on a global bent on contemporary art, but it was during this visit that he decided to re-engage with his Japanese identity and strengthen his commitment to both the high-quality art form of nihonga and the popular culture of anime and manga. On the eve of his departure from New York, while playing a late-night word game with friends using non-sensical words like “dobozite” (a manga word meaning “why?”), Murakami came up with the figure of Mr. DOB, who would later become the artist’s signature character across his diverse array of artistic media. Previously, his work focused on a global bent on contemporary art, but it was during this visit that he decided to re-engage with his Japanese identity and strengthen his commitment to both the high-quality art form of nihonga and the popular culture of anime and manga. On the eve of his departure from New York, while playing a late-night word game with friends using non-sensical words like “dobozite” (a manga word meaning “why?”), Murakami came up with the figure of Mr. DOB, who would later become the artist’s signature character across his diverse array of artistic media.

In order to produce his otaku-inspired sculptures, Murakami founded the Hiropon Factory in 1996. Like many of Murakami’s works, his factory is modeled on both traditional Japanese art workshops, such as those that produced colorful woodblock prints from the Edo period, and on Andy Warhol’s Factory. At Hiropon, assistants trained in various areas of expertise work together under the artist’s supervision for large-scale, mass-market projects. In 2001, the Hiropon Factory became Kaikai Kiki Co., a highly organized company with about fifty employees in its Tokyo headquarters, and twenty in its New York office and studio. Apart from producing and marketing Murakami’s works, the corporation promotes new artists; operates art fairs; organizes collaborative projects with individuals and companies in the fields of fashion, music and entertainment; and develops animated videos and films. Kaikai Kiki represents a shift in the production of modern artwork, where fine art and commerce are seamlessly integrated, and where the physical hand of the artist in the making of the artwork no longer determines the financial value, but rather the symbolic value is created through an artist’s association with the art-commodities produced in his business-oriented factory. Now the corporation employs as many as 60 full time employees in its Tokyo location, and more than 20 in New York.

In 2000, in search of the Japanese post-war identity and out of frustration with his compatriots’ indifference to Japanese contemporary art, Murakami presented Superflat’s theory in a group exhibition of the same name. The exhibition included his own works as well as those by Yoshitomo Nara, Shigeyoshi Ohi, Aya Takano and others. Superflat theory soon swept across the world of contemporary art, becoming a landmark movement in contemporary Japanese art, the latest major style to be internationally acclaimed in the art world since the 1950s by the Japanese Gutai group.

Murakami’s historic essay, “A Theory of Super Flat Japanese Art” (2000), is the ultimate expression of his early disdain for the art world. It expresses the desire to create a uniquely Japanese art form that is directly related to the long shadow of Japan’s trauma after the humiliating defeat of the Second World War. This essay seeks to extract the very core of Japanese post-war culture in order to use it as a foundational philosophy for his works of art. As Pico Iyer points out, Murakami “is a realistic chronicler of the flight from the real. And just as Andy Warhol decided to give modern America exactly the glut of mass production and mass celebrity that he seemed so intent on, with vengeance, so Murakami offered Japan precisely the images that he loves, in his fondness for the kawaii and those deviant forms that he loved the otaku.” The Japanese version of this essay shows a vitriolic anti-Americanism, while his English translations focus on it.

His epic Superflat thesis aims to seamlessly unite the history of Japanese art from 12th and 13th -century Genji and Heiji scrolls with contemporary Japanese pop-culture. Despite his art-historical and culturally-rich referents in his art, essays, manifestos, and interviews, people are often immediately drawn to his work for its seeming superficiality and dazzling explosion of characters and colors. This paradox between the profound meaning and the immediate pleasure enjoyed by his audience directly expresses of the fluid nature of his Superflat concept.

Current Practice

Since the founding of the Hiropon Factory, Murakami’s projects have been more commercially charged and explored unconventional artistic media, including fashion, music, entertainment, public installations, animation and film. This shift between roles reveals Murakami’s ambition to redefine what a postmodern, international artist can be.

In 2002, at the invitation of designer Marc Jacobs, Murakami began a long-term collaboration with the elite fashion brand Louis Vuitton. Murakami was able to tweak the brand to incorporate its own unique aesthetics without losing its identity in the LV project. For example, he combined LV’s monogram with his own signature jellyfish eyes, or he overprinted the monogram with his cartoon cherries. This collaboration made Murakami widely known for further blurring of commercial boundaries, elevated Murakami’s status to fame in his home country, and raised the economic value of his art to one that is highly valued among (mostly Western) collectors.

His fame in the fashion world also swept across the pop music industry. In 2007, Murakami designed the Dropout Bear character for Kanye West’s Graduation album, and directed an animated video for West’s Good Morning song. His collections in the world of pop music include South Korean superstar G-Dragon and Pharrell Williams, who also collaborated with Murakami in 2009 and 2014. Murakami later “re-appropriated” these projects by incorporating the identical imagery into his paintings and sculptures meant for prestigious art institutions or influential collectors.

Takashi Murakami

村上 隆