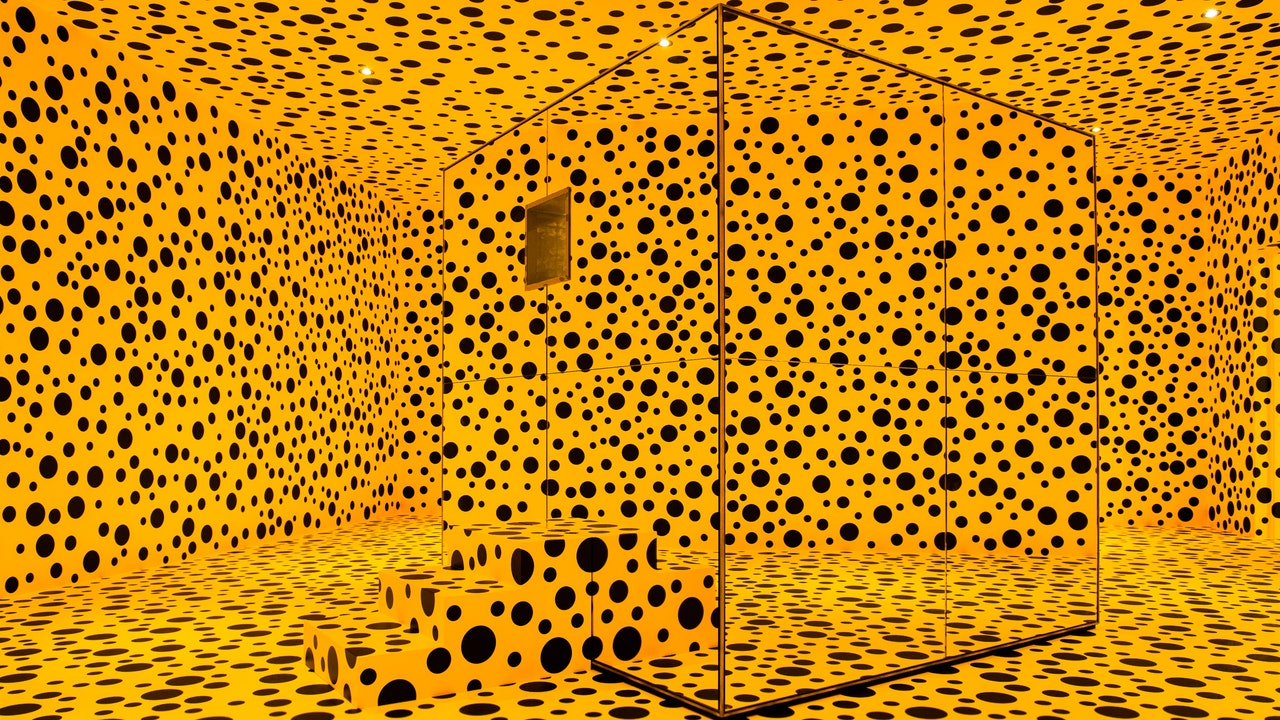

Over the last five years, more than 5 million museum visitors have queued – and queued up a few more – for a quick glimpse of Yayoi Kusama’s work. The 89-year-old Japanese artist, who has stayed willingly in a mental hospital for the past 41 years, has had large-scale solo exhibits of her work in Mexico City, Rio, Seoul, Taiwan and Chile, as well as big tour exhibitions in the US and Europe. Last year, she opened her own five-story gallery in Tokyo. The Large Museum in Los Angeles recently sold 90,000 $25 tickets in the afternoon to its Kusama show, leading the LA Times to ask if the artist was “Hotter than Hamilton?”

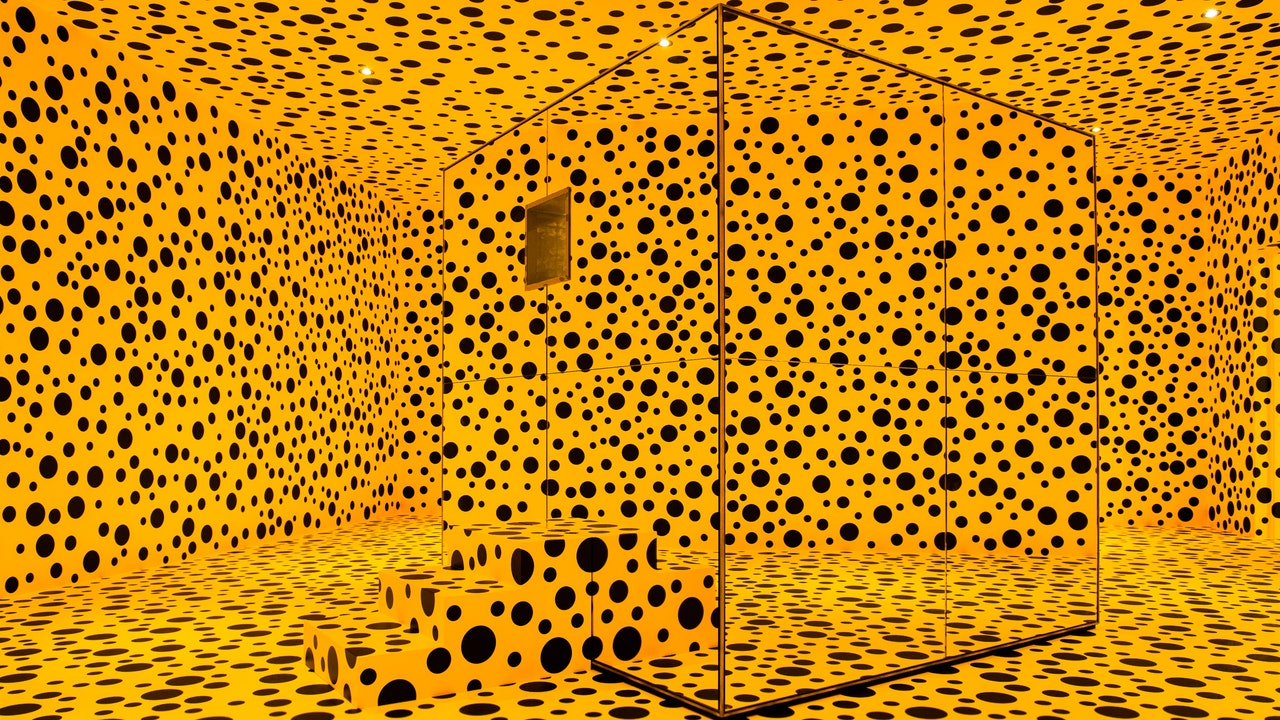

As the numbers have gone up, so the time that any visitor will spend in Kusama’s installations—the interactive “infinity mirror rooms” with colored lights and painted pumpkins and polka dots that represent forever—has gone down. In 2013, the David Zwirner Gallery in New York reduced time slots to 45 seconds for each viewer. Five years later, tourists to the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., who had been queuing for more than two hours, were down to half a minute.

When did this happen to you? The most obvious single word to answer is “Instagram.” People – hundreds of thousands of them (see #YayoiKusama or #InfiniteKusama) – take pictures of themselves in Kusama’s special spatial wonderland and share the results. Many contemporary art galleries are currently discussing the concept of an exhibition as a “experience” of uploadable social media. Kusama – in creating a concept that she first proposed in New York in 1966 – has already cornered the market. Kusama confidently took the decision to leave Japan to go to New York though that was a fairly surprising thing to do. Heather Lenz, Director Speaking on the phone last week, Lenz admitted that the smartphone-friendly nature of the job is obviously part of the draw – but said it could only lead to a deeper understanding of Kusama’s career.

“Most people have seen her work on Instagram,” Lenz says, “but when they hear what she has had to do to achieve the success that has eluded her for so long, they just have to do with it. We did a few screenings, and while most people knew about the job, only two people in the audience knew, for example, that she was staying in a psychiatric hospital.” Lenz’s film shows how Kusama’s life was, if anything, more extensive than her obsessive work, and how one tells the other. It does no harm as a tale of perseverance and victory that it falls into the tidy chapters of Kusama’s self-transformation.

In the first of these, Kusama’s childhood, the curious seeds of the art world’s favorite selfie-craze were seeded. Kusama was born into a wealthy family in rural Japan who operated extensive plant nurseries, growing varieties of violets and peonies and zinnias to be sold all over the world. From a very young age, Kusama would take her sketchbook down to the seed-harvesting grounds and sit among the flowers until, as in a fairy tale of the kind of Grimm, one day she saw the flowers crowding in and talking to her. “I thought that only humans could talk, so I was shocked that the violets used words. I was so frightened that my legs started trembling.” This was the first in a series of terrifying hallucinations – she calls them depersonalizations – that haunted her childhood. These episodes seem to have been linked to the dislocations of her home life. Kusama grew up in a very dysfunctional household. Her father was a philander, and her mother sent Kusama to spy on him with her mistresses, but when she reported back, she recalls in her autobiography, “My mother was going to vent all her rage on me.”

“My mother was against me being an artist. She just wanted me to marry a rich man.”

Her mother tried to stop Kusama from painting – ripping the canvas out of her hands and smashing it – demanding that she learned etiquette to make a successful marriage. Kusama kept drawing. It was her way of making sense of her hallucinations: the flowers of the tablecloth that enveloped her and chased her upstairs; the unexpected shimmering of the sky. “When things like this happened, I would hurry back home and draw what I saw in my sketchbook… recording them helped to ease the shock and fear of the episodes,” she remembers.

It seems that many of the motifs that have become her trademarks have been embedded in this tradition. The first Kusama pumpkin to see was with her grandfather. When she went to pick it up, she started talking to her. It was the size of the head of a guy. She decorated the pumpkin and received an award for it, her first 11-year-old. Eighty years later, her biggest silver pumpkin sculptures were sold for $500,000.

After the assault on Pearl Harbor, when Kusama was 13, she was forced to work in a factory making parachute fabrics. She painted intricate flowers over and over throughout the evening. In a notice of her first show, the local paper reported her producing 70 aquarelles a day

Watching the stills of Kusama’s early life in Lenz’s documentary – her hair cut straight across her forehead, photographed between flowers – is a sharp and moving contrast to the footage of the artist at work in her studio. The same slightly bulbous eyes look out from under the red wig as she connects her dots with a magic marker, chewing her lip like a girl. “To me,” Lenz says, “Kusama’s childhood trauma was instrumental in her work, not only because of her difficult family, but also because of her society and the nightmare of the Second World War.”

Lenz came to understand these stresses more profoundly because, when making a film, she married from a Japanese family and heard the story of her husband’s grandfather, killed by the Hiroshima bomb, and her mother-and father-in-law, who had an arranged marriage. “That gave me a better understanding of her childhood,” she says. “The standards of the time for a young woman, an arranged marriage, children. Kusama confidently took the decision to leave Japan and go to New York though it was a fairly surprising thing to do.”

The second chapter of Kusama’s journey started when she first visited Georgia O’Keeffe’s work in a bookshop in Matsumoto, her hometown. She found O’Keeffe’s address in New Mexico, and wrote to her for advice on how to make her way into the art world of New York, sending some of her own intricate aquariums of abstract vegetal shapes and bursting seed pods. O’Keeffe answered, puzzled at first why anyone, let alone a young woman in rural Japan, would want to do such a thing, but the interest has grown over a number of years into a kind of mentorship. “The artist has a hard time making a living in this country,” O’Keeffe answered. “You’re just going to have to find the best way you can.”

Kusama arrived in New York in 1958, at the age of 27, with a few hundred dollars sewn in the linen of her dresses, along with 60 kimonos of silk and some sketches. Her intention was to survive the sale of one or the other. In her own account, she initially subsisted on food scraps, including fish heads scavenged from the fishmonger’s trash, which she boiled for soup. She’s been following her job around the area. “One day,” she recalls in her autobiography, “I brought a canvas more than 40 blocks in the streets of Manhattan to present it for consideration at the Whitney Annual. My painting was not chosen, and I had to take it back 40 blocks. The wind was blowing hard that day, and more than once it looked as though the canvas was floating up into the air, taking me with it. When I got home, I was so tired that I slept like a dead man for two days.”

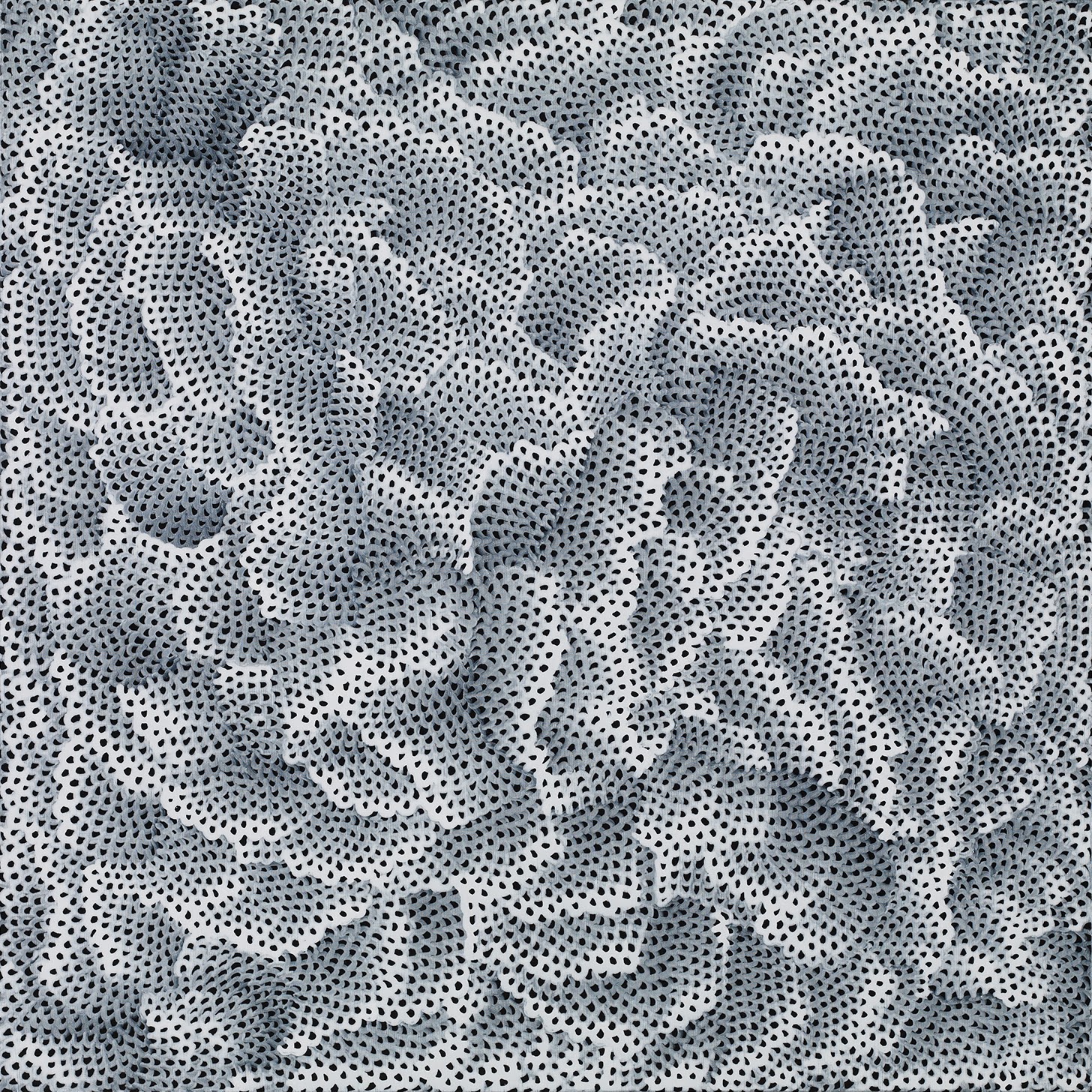

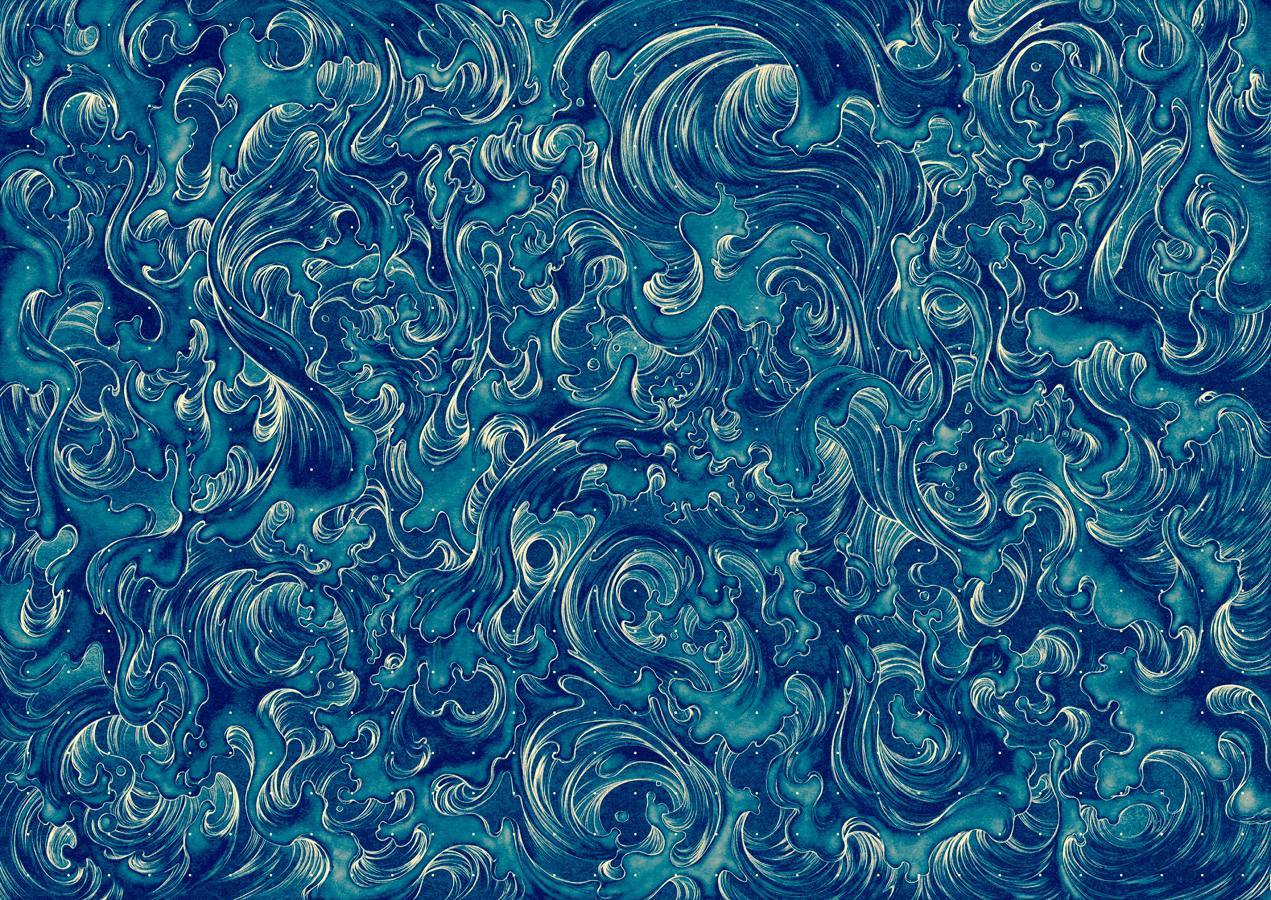

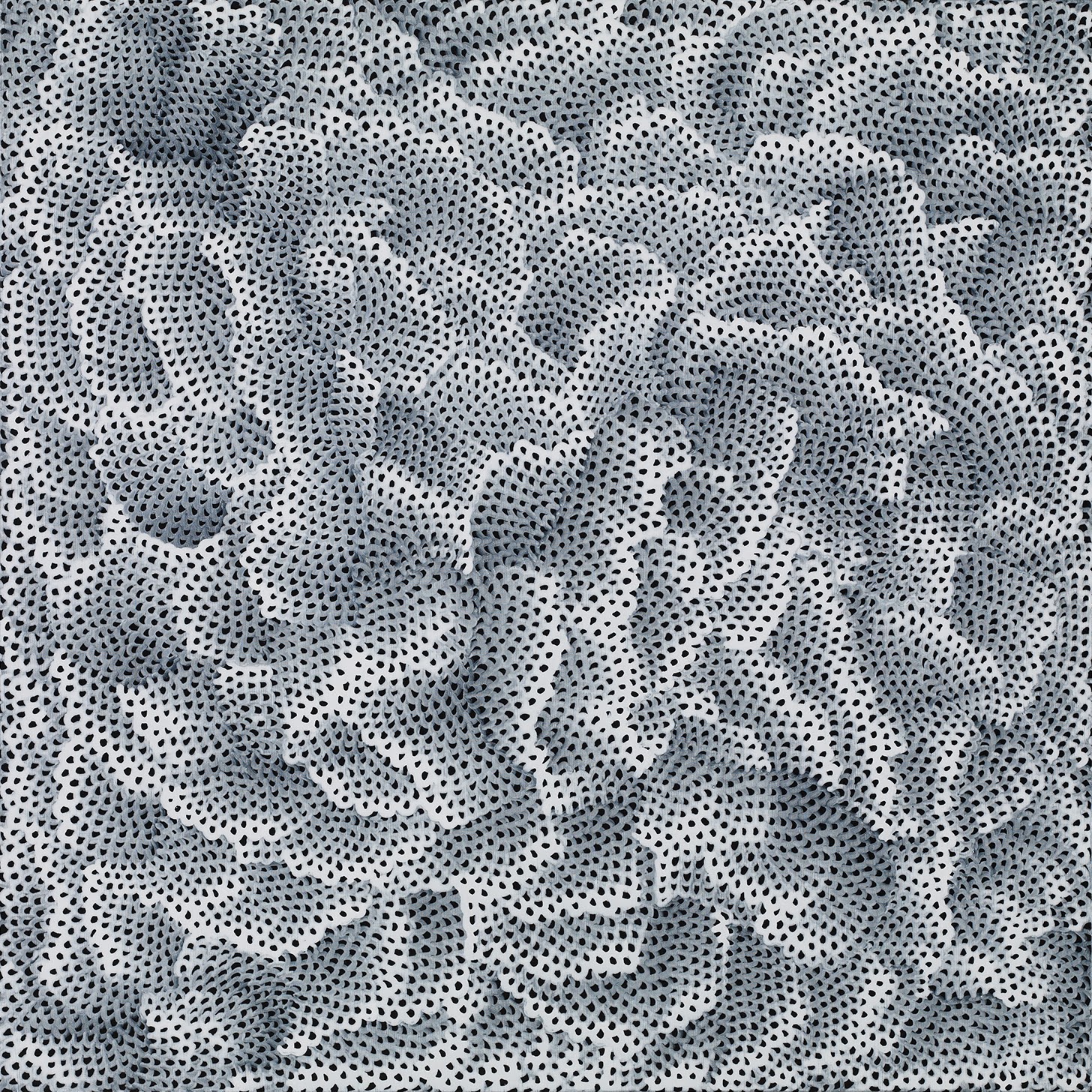

Her breakthrough pieces, the Infinity Net paintings, originated from an earlier collection of aquariums called the Pacific Ocean, which she had made in response to the tracery of waves on the surface of the sea when she first flew from Tokyo. The nets she painted were made of a repetitive singular impasto gesture in small circles, like interlocking scales; the longest canvases were 30ft in length. One of these canvases sold for $7.1m in 2014, a record for a living female artist. The first ones she sold for $75 to fellow artists Frank Stella and Donald Judd in 1962.

Judd and Kusama have been living in the same building on 19th Street in Manhattan for a while. “She’d sit around my apartment and talk, or I’d go down there and talk,” Judd said in a 1988 interview. “She must have worked through the night, as far as I could tell. Most of the paintings were done in one take. I don’t understand how she’d be able to do that, but she’d start in the corner and then go over.” One of the startling aspects about seeing Lenz’s film is the way Kusama appeared to be written out of the history of pop art. There was a period in the 1960s when she shared nearly equal billing – and popularity – with the likes of Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg. Part of this eclipse seems to have been by design – Kusama has long said that the Waspish men around her appropriated her original ideas and moved away as their own.

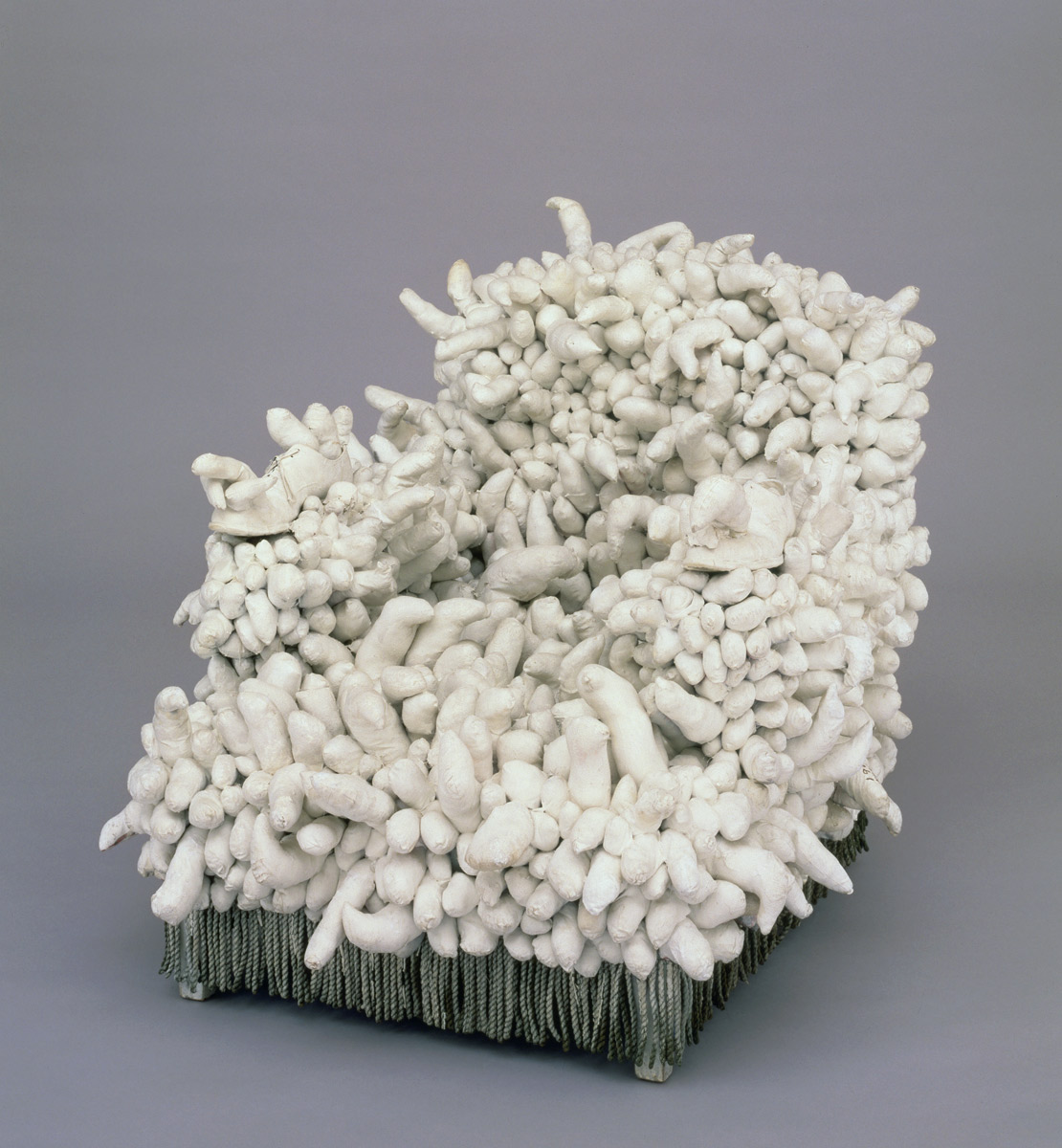

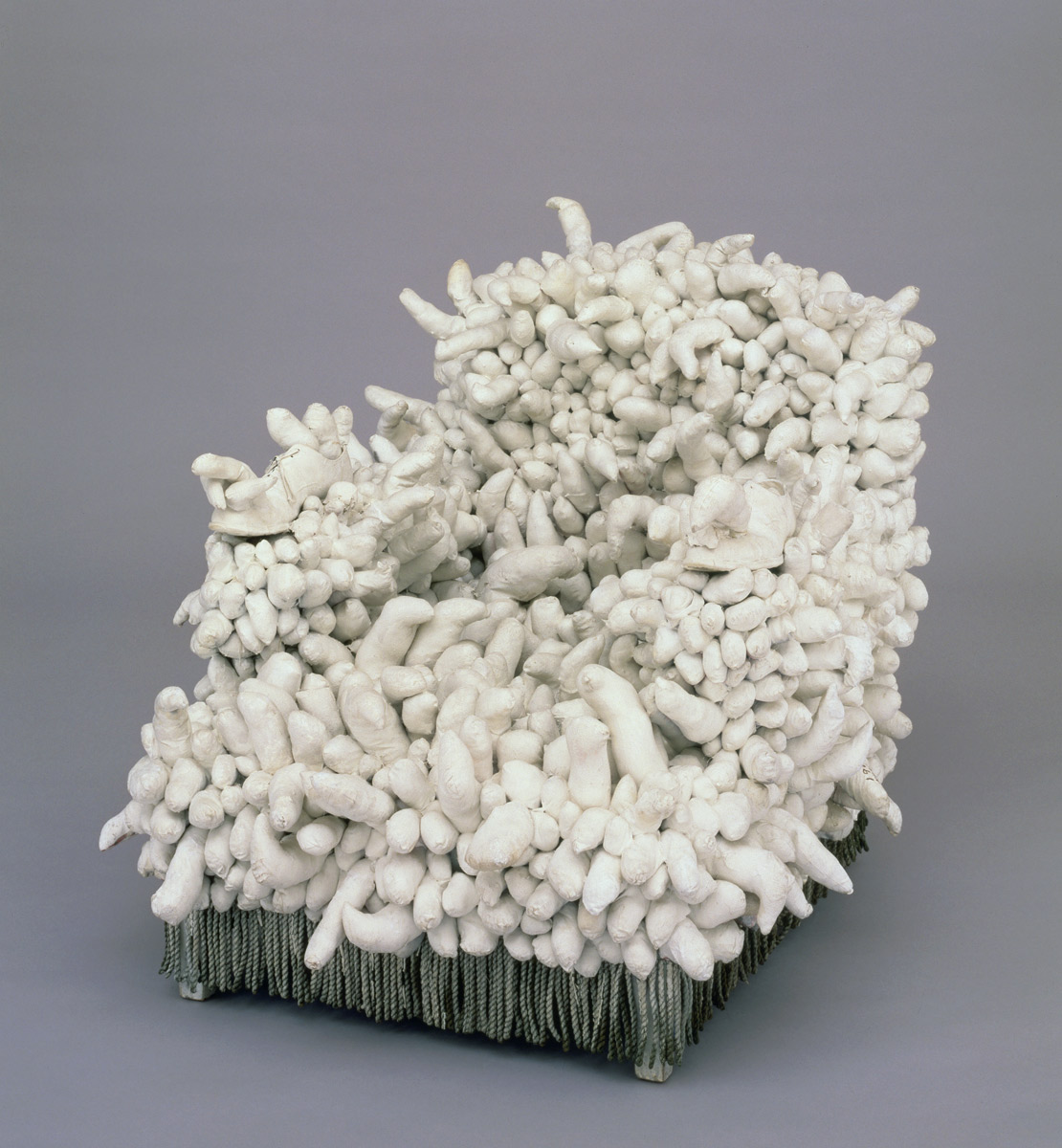

In 1963, she began to create chairs and other objects decorated, fungi-like, with white painted phallic shapes made of stuffed fabric; her piece of resistance was a rowing boat, complete with oars, which she and Judd rescued from a junkyard. It was presented in a box-like room, the walls, the ceiling and the floor of which were papered with 999 silk-screen images of the phallic ship. She saw this as her own private aversion therapy.

“I started making penises to heal my feelings of disgust with sex,” she wrote later. “My fear was the hide-in-the-closet-trembling sort. I was told that sex was filthy, shameful, something to hide. Complicating matters even more was all the talk of ‘healthy families’ and ‘arranged marriages’ and the utter resistance to romantic love… I also experienced a sex act when I was a toddler, and the terror that came through my eye blew up inside me.” There is a grim irony in this act of therapy in that Oldenburg seems to have embraced her soft sculpture technique and Warhol’s repeated wallpaper prints. She was desperate at the way the men around her sought fame for her theories.

Lenz’s film aims to reveal this appropriation. “Every single Q&A I get a question about how true the allegations that these white male artists stole her ideas were,” Lenz says. “Obviously, I’ve reviewed all the dates, and they’re all working out like she said. People who had degrees in art history always questioned this, though; it was as if they didn’t want to change their mind. They know what they know, I suppose.” Kusama saw something like her ideal man in Joseph Cornell, the reclusive genius of the outer world of art, the founder of surreal boxes of found objects, and a man who had always lived with his mother in the 1950s. Cornell became fascinated with Kusama, giving her a dozen poems a day, never hanging from a phone call, so he was there when she picked it up. This was her only known romantic relationship, though, “he didn’t like sex, and I didn’t like sex, so we weren’t having sex.” He wasn’t a very easy guy.

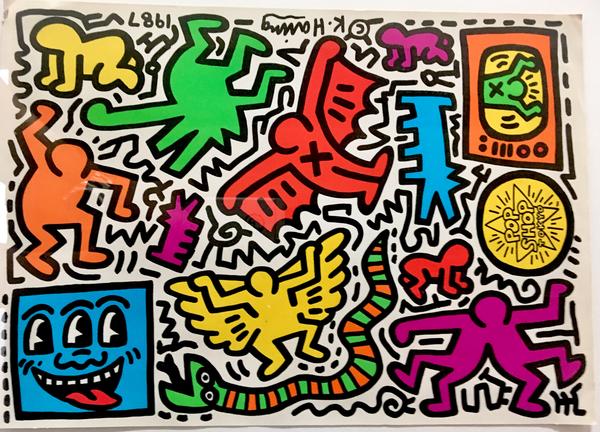

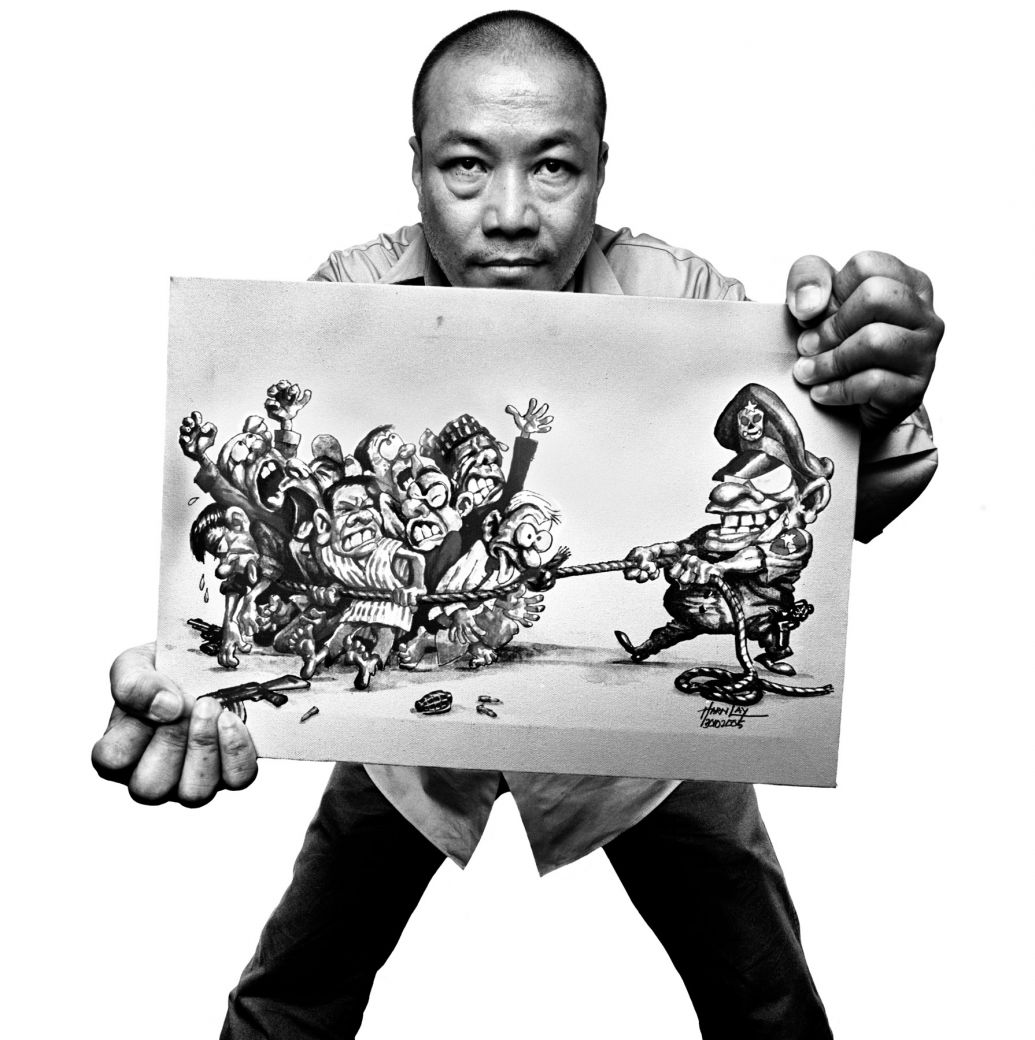

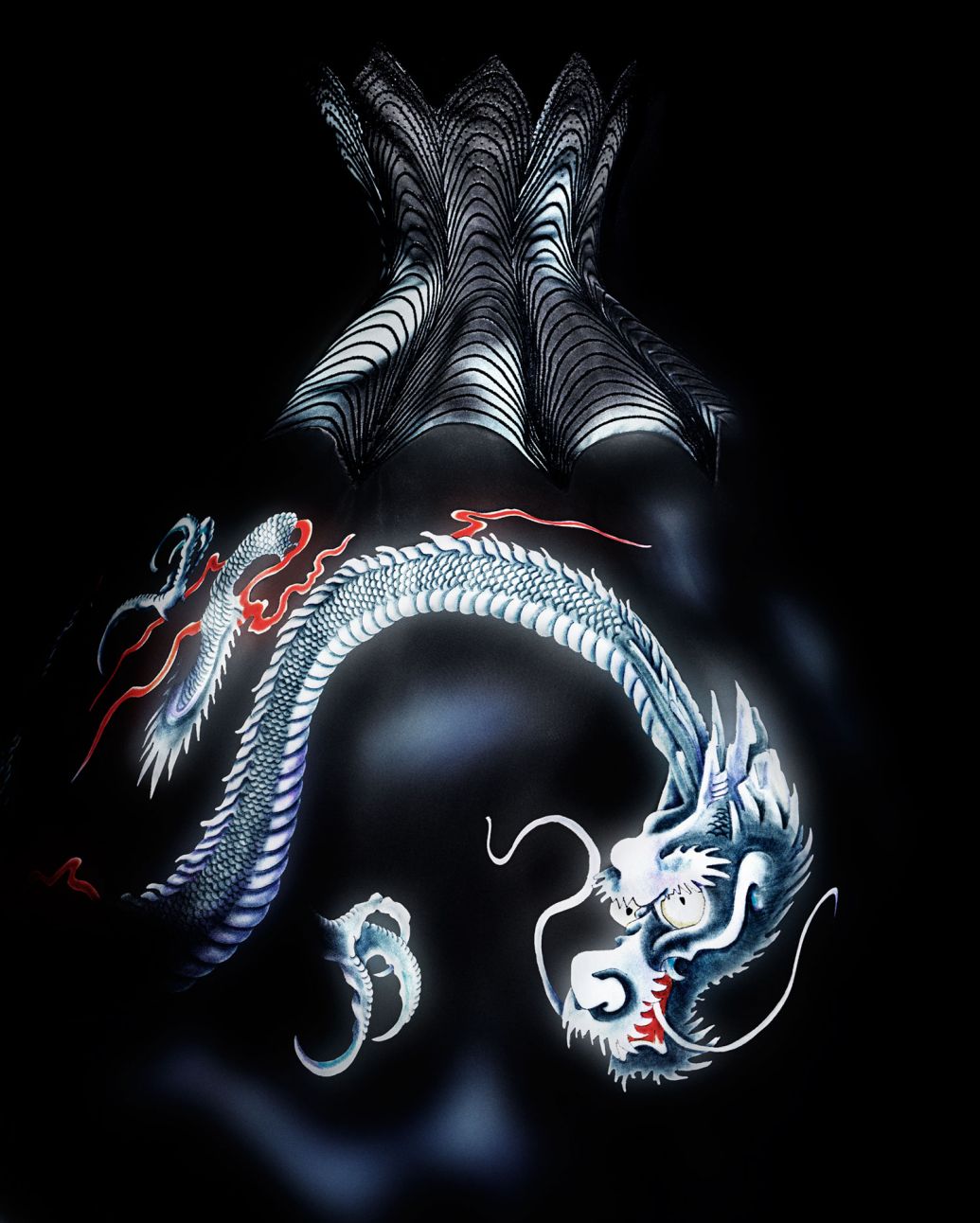

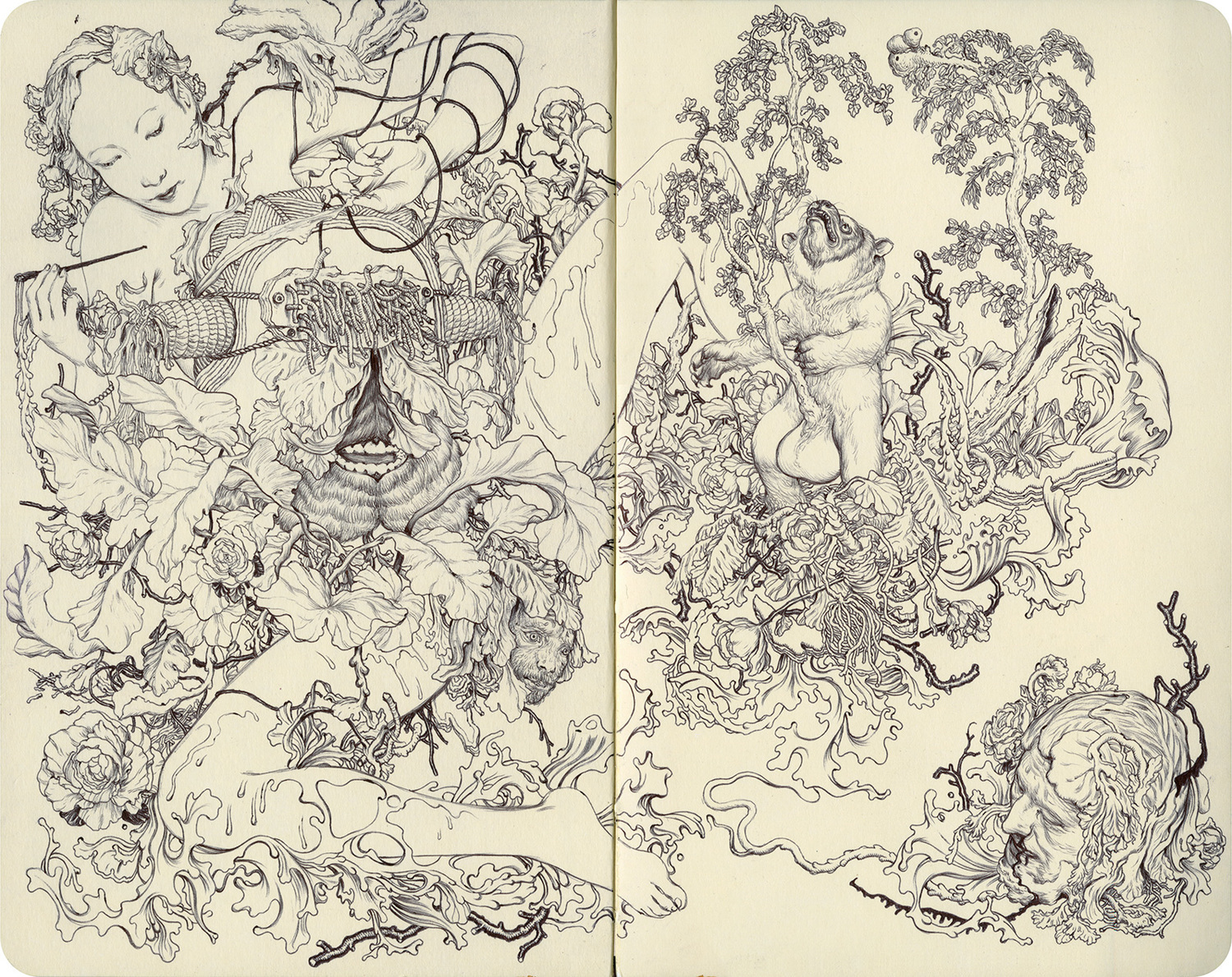

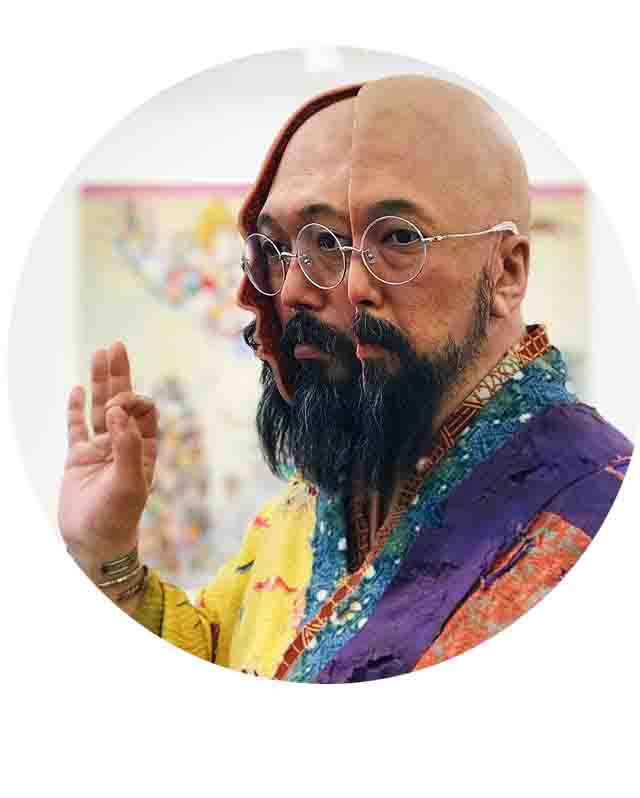

Takashi Murakami

Takashi Murakami

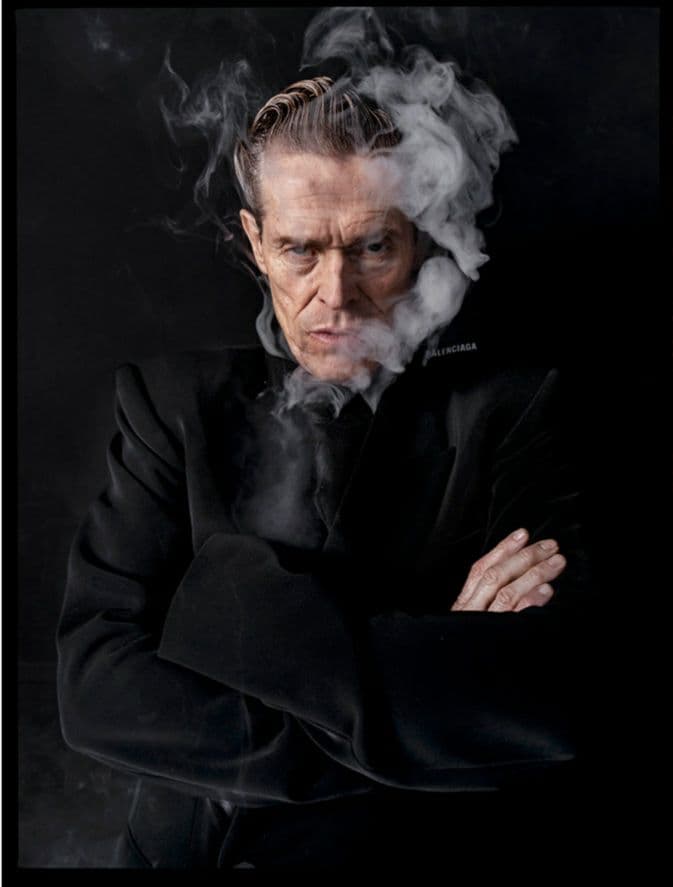

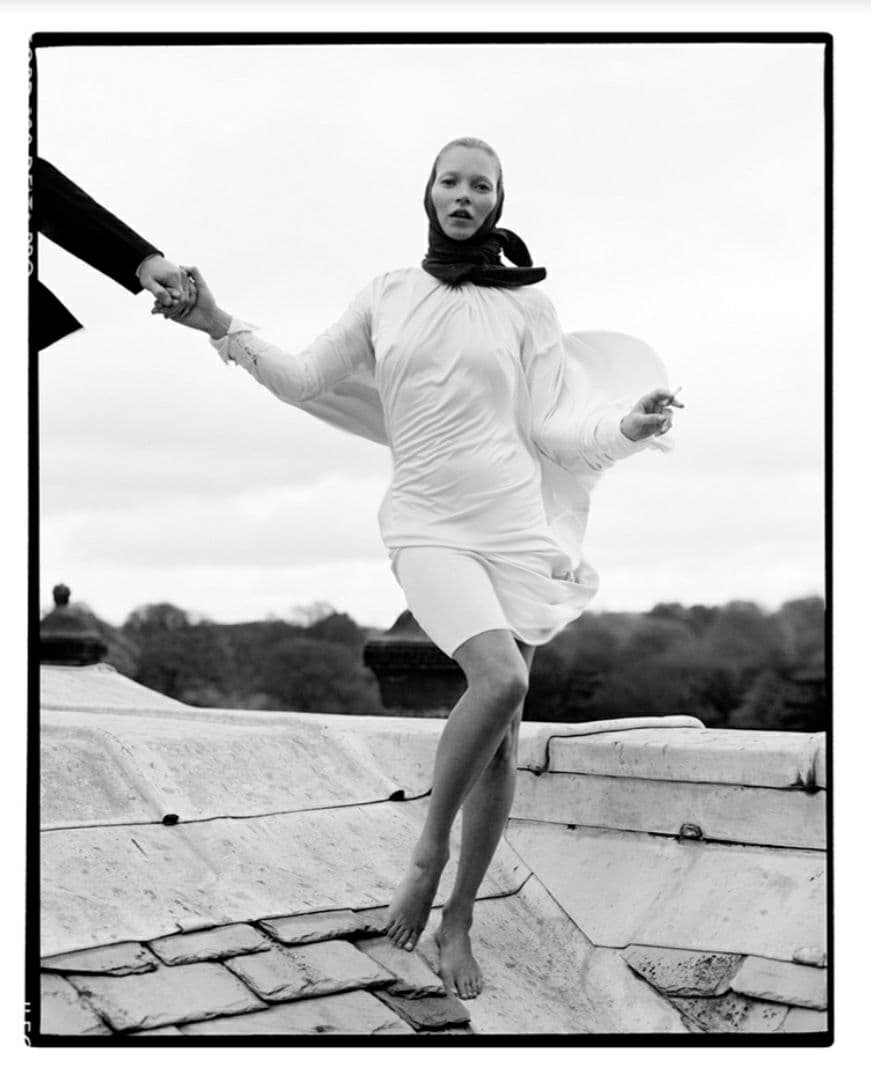

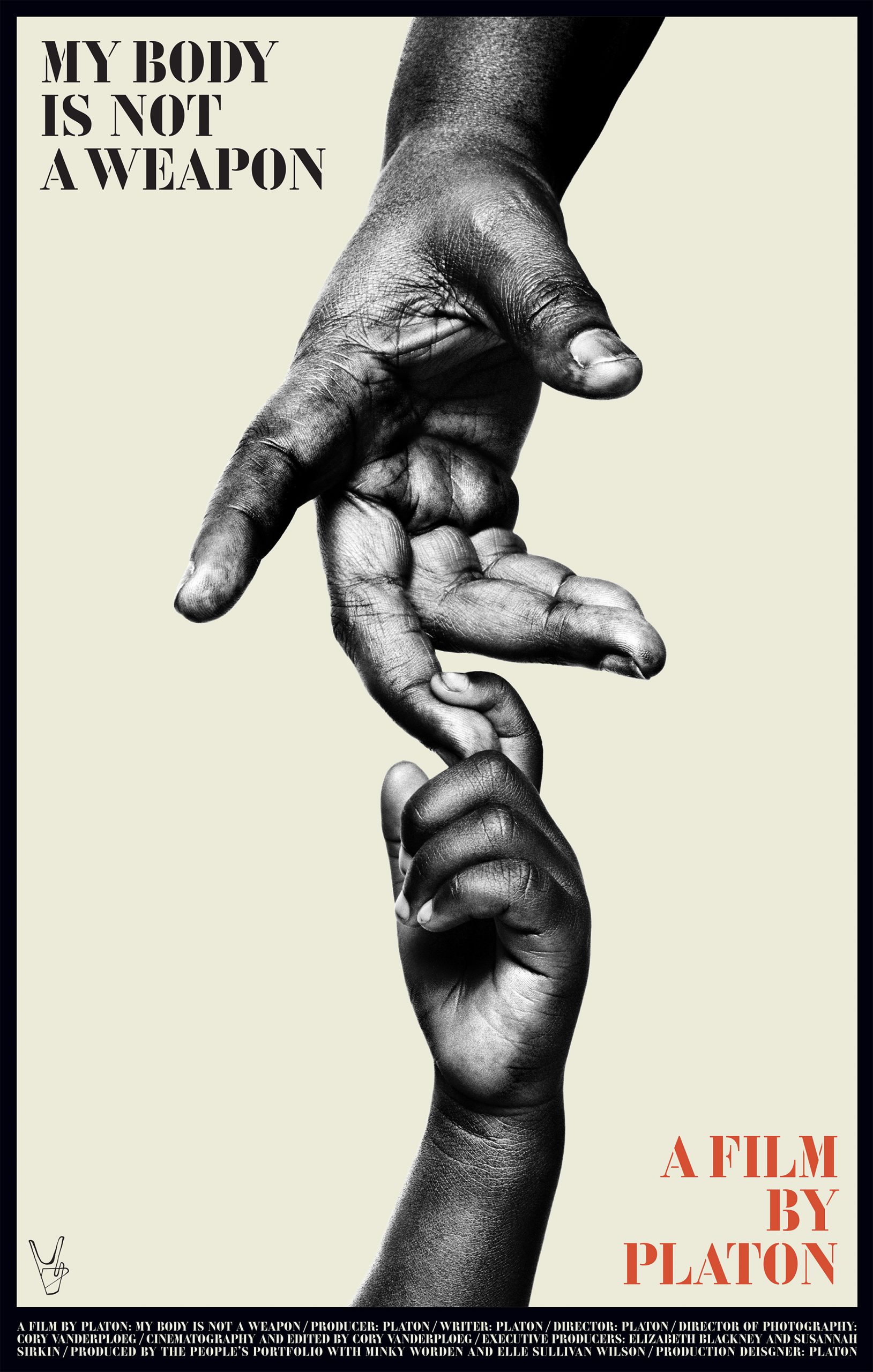

Walker’s photos have reached Vogue readers for more than a decade, month after month. His unmistakable style is characterized by lavish staging and dramatic motifs. After 15 years of emphasis on photographic stills, Walker is now also making moving video.

Walker’s photos have reached Vogue readers for more than a decade, month after month. His unmistakable style is characterized by lavish staging and dramatic motifs. After 15 years of emphasis on photographic stills, Walker is now also making moving video.